Sovereignty is a concept that operates across all tiers of existence and identity. I am sovereign as an individual. My power lies in my ability to freely exert my will toward a chosen action or goal, and to withhold that will from what is undesired or compelled. Sovereignty, in this sense, is inseparable from interest: it is the freedom to marshal one’s energy and resources toward one’s aims without undue interference. This understanding extends naturally from the individual to the family, the community, and ultimately, the nation.

Questions of sovereignty arise most sharply when the individual subordinates their will to the interests of a collective. The family, for instance, is a fundamentally communal unit. Its survival depends on contribution from all members—child and adult, male and female—governed by a principle akin to “from each according to ability, to each according to need.” Yet contribution is never neutral; it is assigned.

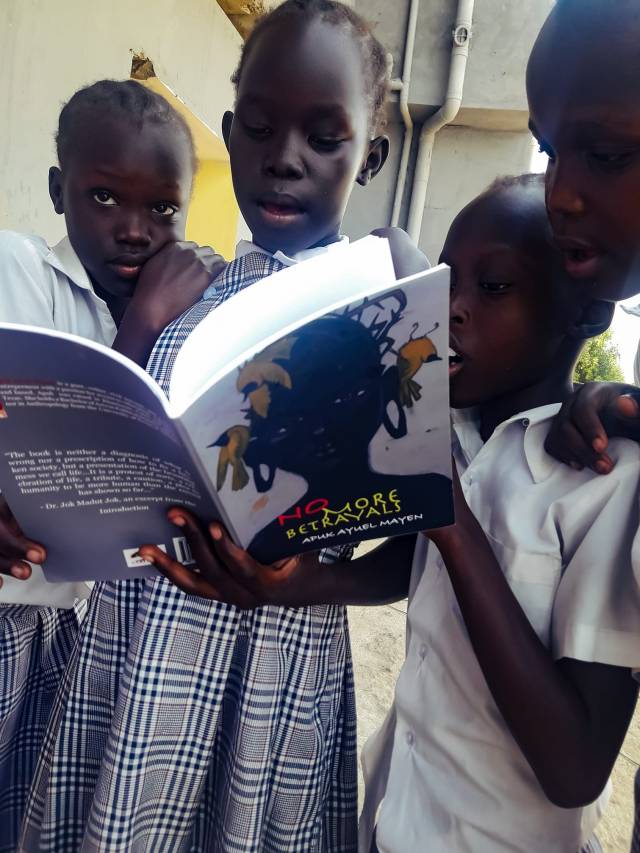

I recall stories from my father’s generation about the arrival of mission schools—modernity arriving quietly, yet decisively. Families faced choices about who would be sent to school. Not the strongest, for they were needed to defend the clan. Not the weakest, for they required protection. Not the just, for they would one day adjudicate disputes. And not the girl child, for she was wealth—her bride-price sustaining the family and securing its continuity.

What we would now call discrimination was, at the time, a rational calculus rooted in survival. The dictionary defines discrimination simply as the recognition of difference—a sovereign act exercised daily. Politically, however, discrimination acquires a moral dimension: the unjust or prejudicial treatment of people based on categories such as sex or age. Intent and outcome matter. While barring certain children from education may once have served a collective interest, its consequences have been enduring. Education became the gateway to opportunity, and those excluded—especially girls—were left structurally disadvantaged by decisions made in good faith.

At the heart of this dilemma lies the tension between collective interest and individual sovereignty. In the lower tiers of social organization, the individual’s aspirations are often subordinated to the perceived needs of the group. Yet societies evolve. When the calculus changes—when cattle no longer constitute the primary measure of wealth, and education becomes a valued currency—the position of the girl child begins to shift. Today, in some communities, an educated girl attracts higher bride-wealth. In others, girls scarcely out of childhood are bid for in the hundreds of cattle, prized less for their potential than for their bodies’ promise of reproduction.

Is this still a sound calculus?

In a militarized society, where wealth, pride, and survival are deeply entangled, the girl child becomes objectified—currency rather than citizen. Violence follows: girls beaten or killed for eloping, for refusing marriage, for asserting choice. Who defines what is right in such contexts? Those who wield power? Those who guard tradition? Or change itself, which remains the only constant?

South Sudan, as a nation, exists in the uneasy space between tradition and modernity. Survival continues to dictate decision-making. Under the familiar logic of contribution and need, the commodification of women persists. Yet societies do not remain static. They recalibrate as circumstances shift, driven less by abstract notions of rights than by evolving interests. Change, therefore, must be engineered—not imposed sentimentally, but incentivized rationally.

This is where the state’s responsibility becomes unavoidable. Those who wield power must legislate catalysts for change—not through symbolic gestures or numerical inclusion, but through policies that reshape behavior while respecting the core of sovereignty. Incentives must reward adaptation; rigidity must carry consequence.

If the state provides free or subsidized primary education, then leaving a girl child behind should be unlawful. If the law recognizes childhood, then underage marriage must be criminalized. Such measures require negotiation with custodians of tradition, but they are neither alien nor impossible. Rural communities and traditional leaders are not irrational actors; they are sovereign agents deeply invested in the dignity and survival of their people.

What is required is not moral condescension, but an honest recalculation of interests. When education becomes visibly linked to prosperity, resilience, and continuity, attitudes will shift. The girl child’s sovereignty will expand—not in opposition to the family or community, but as a strengthening of them.

Sovereignty, after all, is not diminished when shared wisely. It is preserved.

© Apuk Ayuel Mayen. All rights reserved.